In the last part, we broke the application core out, with layers for entities, usecases, and infrastructure. The example code we used in the last part (without breaking the core out) can be found on Github.

Now let's look at how we can implement the core. I will be using TypeScript here because it has two things that we will make implementing Clean Architecture much easier: types, and interfaces. To add TypeScript to an existing React project, we can simply run:

yarn add -D typescript awesome-typescript-loader source-map-loader

Entities

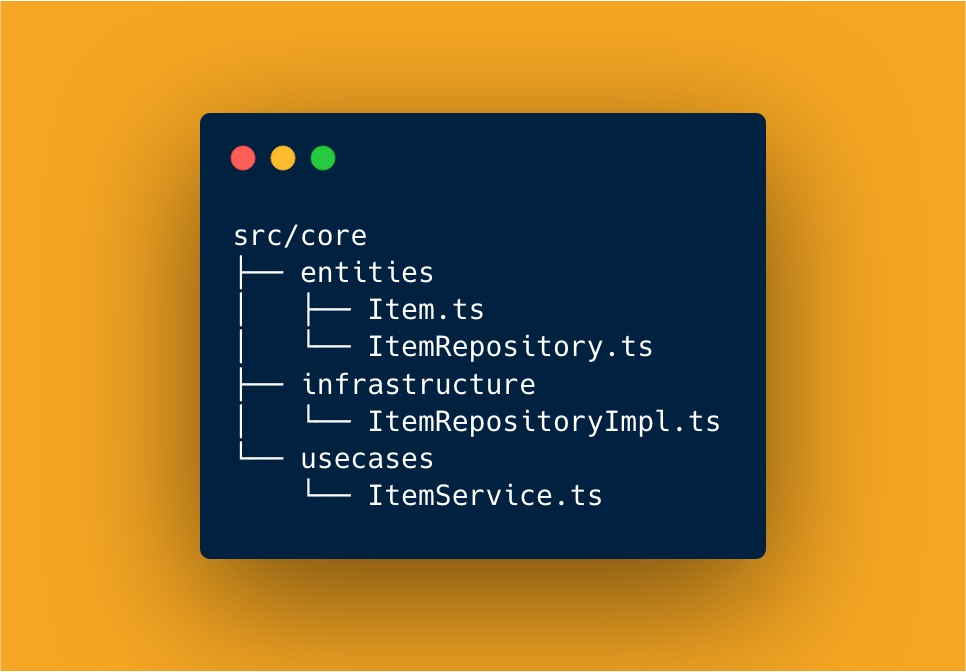

To separate out the core code from the rest of the app, so we'll first create a

subfolder called core, with three subfolders for the Entity, Use Case, and

Infra layers:

src/core

├── entities

├── infrastructure

└── usecases

Inside the entities subfolder, we'll first create the Item class which holds

Item entities. This is a domain entity that will be used throughout the app.

export class Item {

id: number;

name: string;

constructor(id: number, name: string) {

this.id = id;

this.name = name;

}

}

We will also create an ItemRepository interface that will enable us to abstract

out the API calls (and maybe local storage caching later on) which actually get

us the items.

import { Item } from "./Item";

export interface ItemRepository {

GetItems(): Promise<Item[]>;

}

Note how it is returning a Promise (with a list of Items), as it will be an async operation.

Use Cases

Then, we implement the UserService. We are implementing the service after defining

an interface because this will make writing tests etc. easier. There are arguments

against single implementation interfaces, but that is a debate for another time. The

service simply gets the items from the repository and returns them.

import { Item } from "../entities/Item";

import { ItemRepository } from "../entities/ItemRepository";

export interface ItemService {

GetItems(): Promise<Item[]>;

}

export class ItemServiceImpl implements ItemService {

itemRepo: ItemRepository;

constructor(ir: ItemRepository) {

this.itemRepo = ir;

}

async GetItems(): Promise<Item[]> {

return this.itemRepo.GetItems();

}

}

Notice how the constructor of the service takes an item repository. This is the runtime

injection of dependencies that makes this super exciting. We can swap implementations

at runtime and the service has no hard dependencies on infrastructure code, instead

relying on an interface defined at the entity layer.

Infrastructure

Finally, we implement the UserRepository we defined in the entity layer. It will

just be a simple API call using fetch(). We should add error handling here, but I've

left it out for now for the sake of simplicity.

import { Item } from "../entities/Item";

import { ItemRepository } from "../entities/ItemRepository";

class ItemDTO {

id: number = 0;

name: string = "";

}

export class ItemRepositoryImpl implements ItemRepository {

jsonUrl = "...";

async GetItems(): Promise<Item[]> {

const res = await fetch(this.jsonUrl);

const jsonData = await res.json();

return jsonData.map((item: ItemDTO) => new Item(item.id, item.name));

}

}

Note how we are defining an ItemDTO here. This is your contract with the API, and will

change with time. The following line:

return jsonData.map((item: ItemDTO) => new Item(item.id, item.name));

is also very important. This is where the DTO is being mapped to a domain entity. We can move this transformation to another file as our implementation grows in complexity, as this code is on an architectural boundary and will change quite frequently.

All Together Now

We can now edit our Thunk to use the service instead of directly calling the API:

import {

LIST_LOAD_REQUEST,

LIST_LOAD_SUCCESS,

LIST_LOAD_FAILURE,

} from "./Item.types";

import { ItemServiceImpl } from "../core/usecases/ItemService";

import { ItemRepositoryImpl } from "../core/infrastructure/ItemRepositoryImpl";

export const refreshList = async (dispatch) => {

dispatch({ type: LIST_LOAD_REQUEST });

try {

const itemRepo = new ItemRepositoryImpl();

const itemService = new ItemServiceImpl(itemRepo);

const items = await itemService.GetItems();

dispatch({ type: LIST_LOAD_SUCCESS, payload: items });

} catch (error) {

dispatch({ type: LIST_LOAD_FAILURE, error });

}

};

The first three lines within the try hold the essence of any dependency injection setup:

const itemRepo = new ItemRepositoryImpl();

First, we initalise the repository.

const itemService = new ItemServiceImpl(itemRepo);

Then, we inject it into the service.

const items = await itemService.GetItems();

And finally, we access the methods offered by the service.

It's good to keep these steps explicitly defined, so that the flow is clear and can be changed in the future.

And that's it! We've taken our core out and implemented it in a completely isolated fashion that doesn't depend on infrastructure concerns. This makes things nice and testable (I'll try to add some tests to the repo soon!), and makes you think about the parts of your code that can (and definitely will) change—and how to make sure that change is contained.

This is the reason we do not put SQL in JSPs. This is the reason we do not generate HTML in the modules that compute results. This is the reason that business rules should not know the database schema. This is the reason we separate concerns.

Another wording for the Single Responsibility Principle is: "Gather together the things that change for the same reasons. Separate those things that change for different reasons."

If you think about this you’ll realize that this is just another way to define cohesion and coupling. We want to increase the cohesion between things that change for the same reasons, and we want to decrease the coupling between those things that change for different reasons.

— Uncle Bob

This series of posts is dedicated to Mr. Mahasen Bandara, architect extraordinaire, from whom I had the priviledge of learning about Robert C. Martin and architectural boundaries and a ton of other architectural and programming practicies.