My take on doing 'Clean Architecture' in React (Part 1)

Friendship is magic? Wait till you see Dependency Inversion!

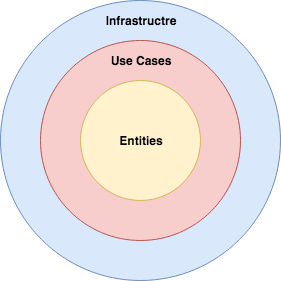

Clean Architecture, simplified.

I'm a huge fan of Robert C. Martin's work in general, and Clean Architecture in particular. I'm frequently on the lookout for how to apply it to the different system architectures and frameworks we work with.

Which modules should be decoupled? I think the rule is similar to the previous rule: Any module that changes frequently should be decoupled from the rest of the system. — Uncle Bob

It's a damn shame that most of the code we are told to write in guides and documentation (often written by people who are heavily invested in the framework that the docs are about) are very tightly coupled to the framework, libraries, and persistence implementation (as well as the REST APIs that are called—how many of us have had to do system-wide changes because the response object from the API changed?)

Today, in part 1 of a 2 part series, I'll write a bit about what I think is a good way to implement Clean Architecture in React JS and React Native apps1.

Why?

The advantages of switching to Clean Architecture are listed out in detail on Uncle Bob's blog, but I am going for three main objectives with regards to having this architecture on our React app:

-

Make the Core 100% testable: All external dependencies (the UI, local storage, REST APIs etc) can be mocked out.

-

Portability: If we need to port the app to Vue JS tomorrow, the core can still be put there wholesale. We can also explore sharing the core between the frontend and backend (if your backend is written in Node or something).

-

Prevent 'Change Propagation': If the REST API's response object changes, or we change the caching mechanism, or any such change happens upstream of the final consumer (the UI), those changes should not cause changes downstream.

Keep in mind that one of the most important fundamentals of Clean Architecture is to recognise where your architectural boundaries are, and to ensure that calls across those boundaries are done using well defined interfaces and contracts. The response object changing does not change the contract, since the core sets the contract and the code that calls the API and parses its responses merely implements it. Your DTO is changing? It's up to the API component to massage that into the existing domain entity, sorry.

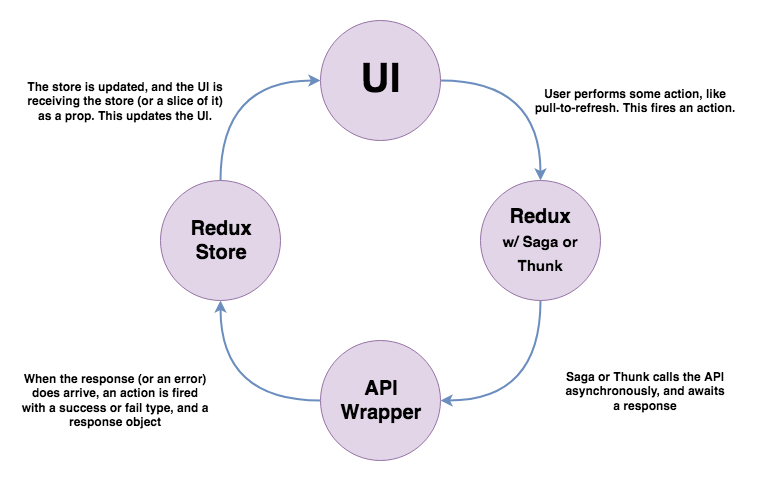

Standard React async call architecture

Okay, so this a very standard and common pattern when writing the most common kind of interface, i.e. call an API, display some data in a component. You could be using Redux for state, or React hooks, or component state, but this diagram barely changes because in essence the user performs an action, which results in an API call, which updates the state and hence the UI.

Your component code would look something like this:

const ItemList = ({ items, refreshList }) => (

<div>

<button onClick={refreshList}>Refresh</button>

<ul>

{items.map(item => (

<li key={item.id}>{item.name}</li>

))}

</ul>

</div>

);

It'll be hooked up to Redux using something like this:

const mapStateToProps = (state) => ({

items: state.items,

});

const mapDispatchToProps = (dispatch) => ({

refreshList: () => dispatch(refreshList),

});

export default connect(mapStateToProps, mapDispatchToProps)(ItemList);

And I'd guess your Thunk (or Saga) would look a bit like this:

export const refreshList = async (dispatch, state) => {

dispatch({ type: "LIST_LOAD_REQUEST" });

try {

const res = await fetch("https://your.api/listdata");

const jsonData = await res.json();

dispatch({ type: "LIST_LOAD_SUCCESS", payload: jsonData });

} catch (error) {

dispatch({ type: "LIST_LOAD_FAILURE", error });

}

};

Pretty simple and familiar, right?

Let's break it 😈

Identifying boundaries

Now, I would like to start off by saying it would be unwise to try to break React and whatever state management solution you use using Clean Architecture. Yes, it's good to keep them isolated but I'd suggest using React patterns such as presentational components and containers to do that—this is because Redux and the ilk are tightly tied to React's Context API, and it would be a massive hassle to handle all that complexity and coupling in our core. So let's keep it out.

I'm thinking of having 3 major components:

- UI: This is in Infrastructure, and is basically React + Redux

- Network and Persistence: Also in Infrastructure. I am thinking of hiding the API complexity behind a repository interface, and to implement local storage for caching if necessary inside this repo implementation itself.

- Application Core: This is in the Use Case and Entity layers, and is where the magical business logic et al. happens.

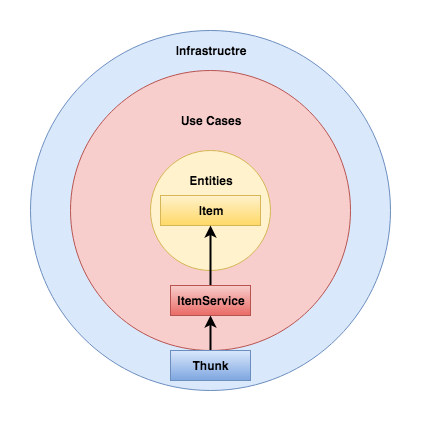

The component diagram, in my head, looks a bit like this:

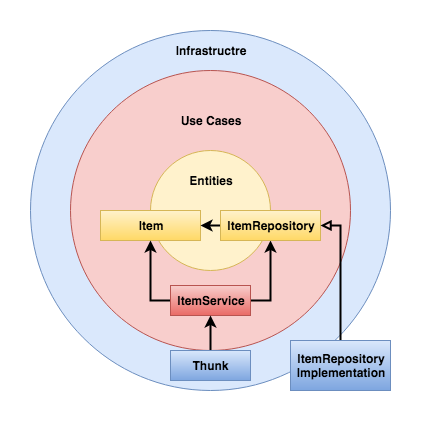

But wait, where's are we calling the API and getting the data for items? We need to

include an ItemRepository interface, and an implementation for it.

This is one of the coolest things about Dependency Inversion, in that all the

arrows are flowing inwards. In this case, ItemService depends on the interface

ItemRepository—which is in the Entity layer—and not on its concrete implementation

which is on a lower layer and will only be injected during runtime. This has several

benefits, which we'll explore in the next part.

The overriding rule that makes this architecture work is The Dependency Rule. This rule says that source code dependencies can only point inwards. Nothing in an inner circle can know anything at all about something in an outer circle. In particular, the name of something declared in an outer circle must not be mentioned by the code in the an inner circle. That includes, functions, classes. variables, or any other named software entity.

By the same token, data formats used in an outer circle should not be used by an inner circle, especially if those formats are generate by a framework in an outer circle. We don’t want anything in an outer circle to impact the inner circles.

— Uncle Bob

The full code for this part can be found on Github.

-

With or without Redux (or Redux-like) state management ↩